photo credit: Michael Nannery

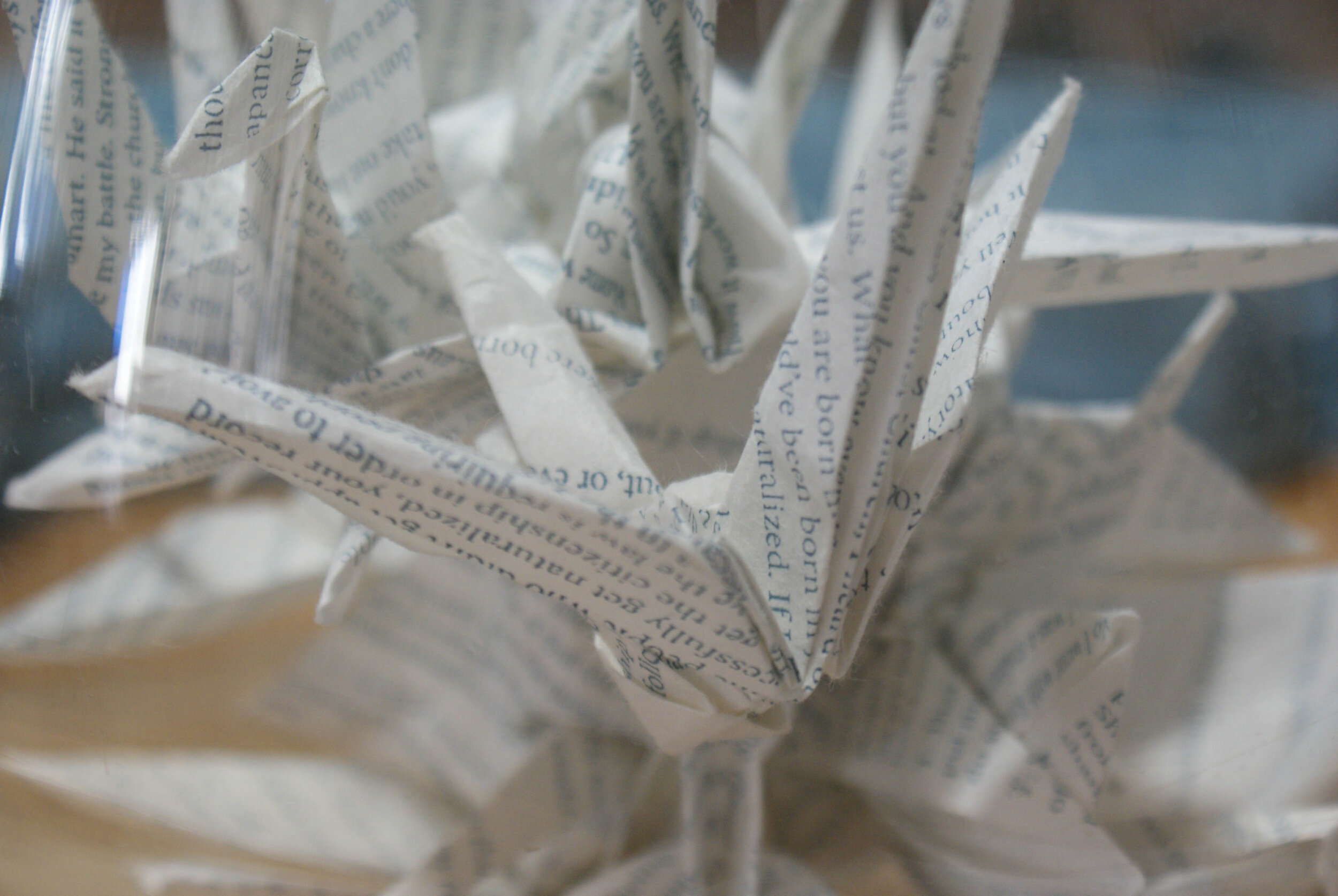

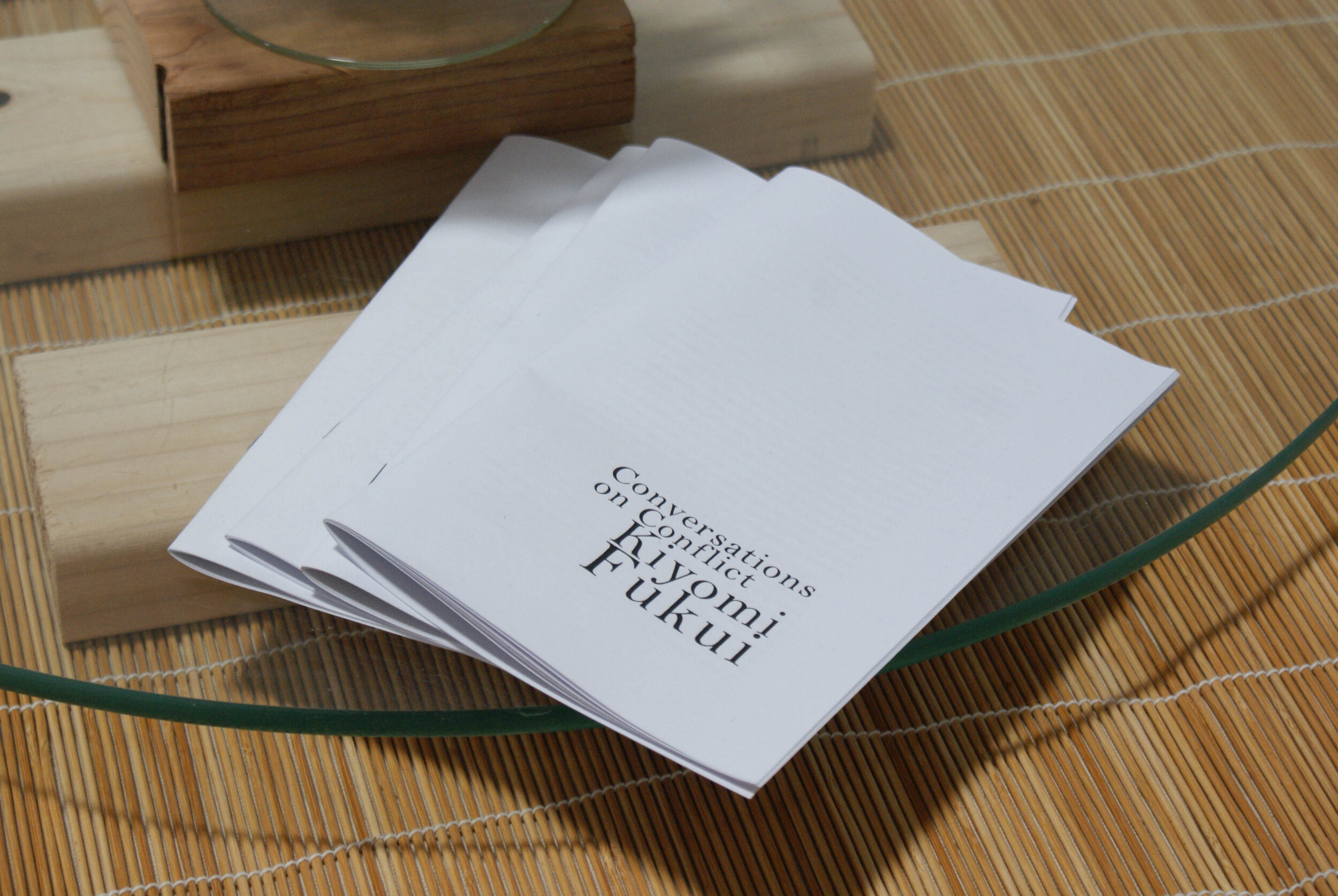

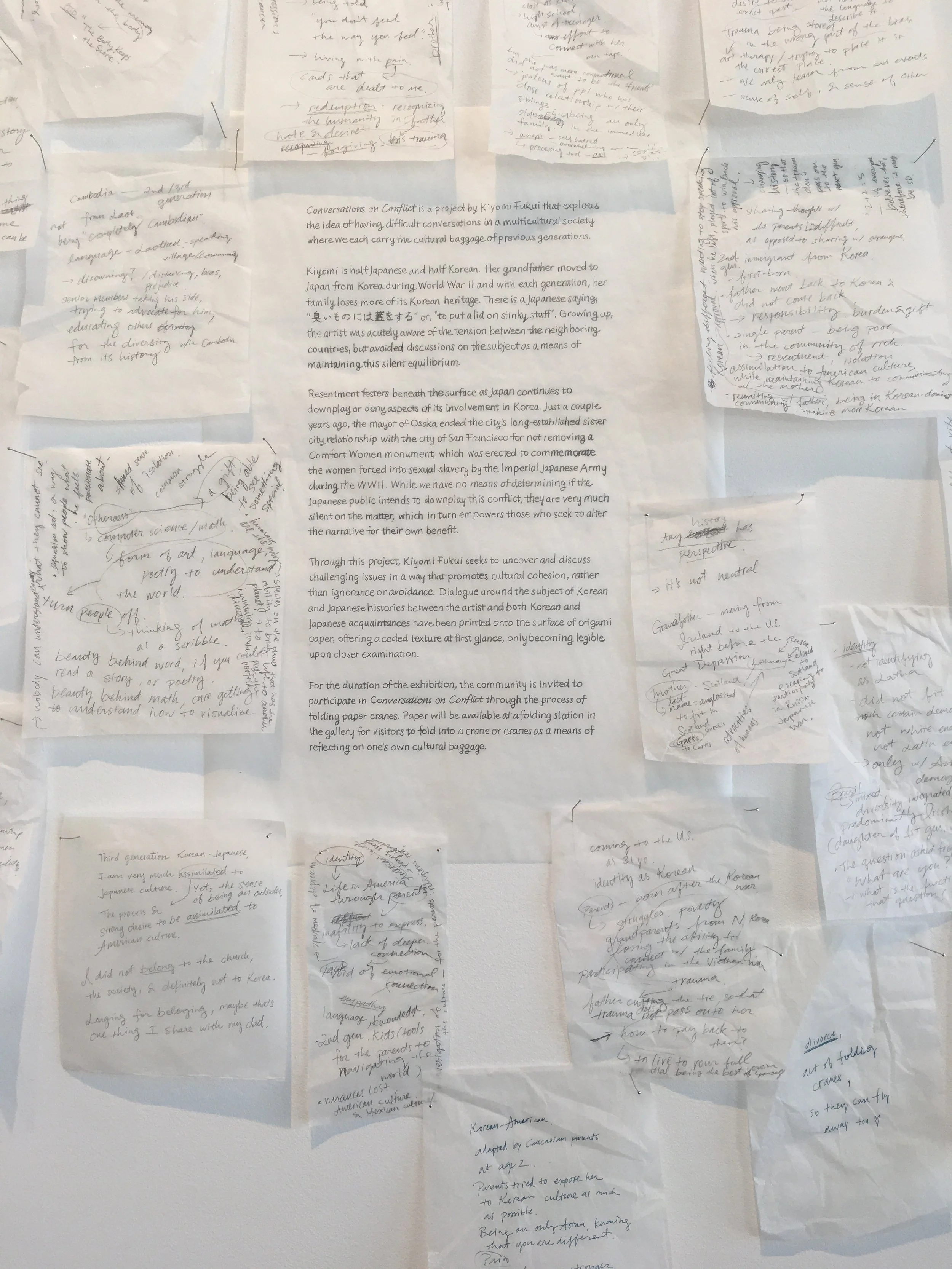

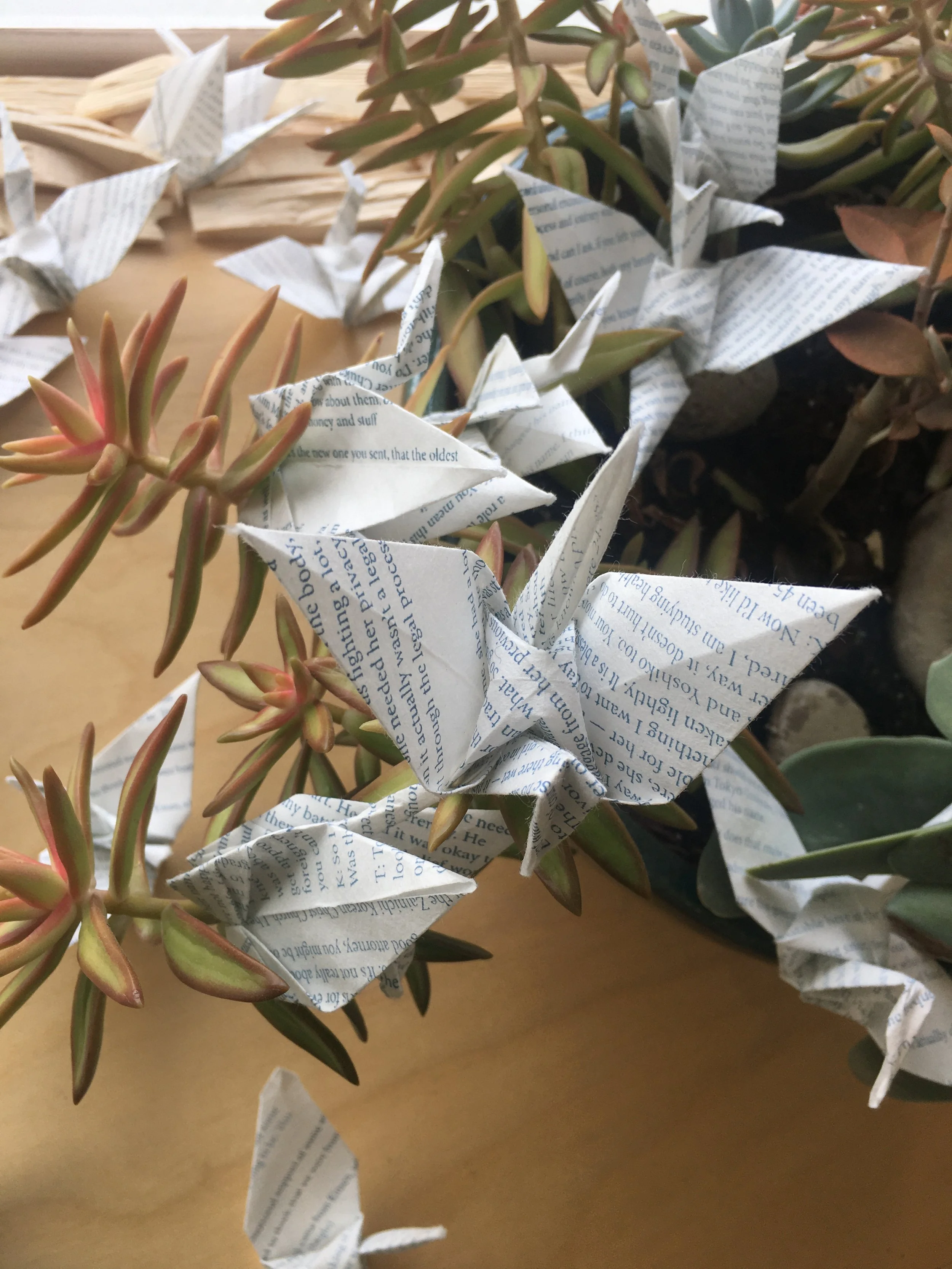

Conversation on Conflict

On a Sunday afternoon, I had a conversation with my father, who has been officially a Japanese citizen for more than forty years by now. Before that, he was what was called Zainichi Korean, which refers to Koreans living in Japan without Japanese citizenship. It is a temporary status similar to a green card. My dad was born and raised in Japan, and does not speak Korean, but only Japanese. He looks just like anyone else in Japan. The definition and number varies, but there are currently more than 300,000 Zainichi Koreans living in Japan. On the record, supposedly my dad is not one of them since the day he became naturalized, along with his dad and his brother.

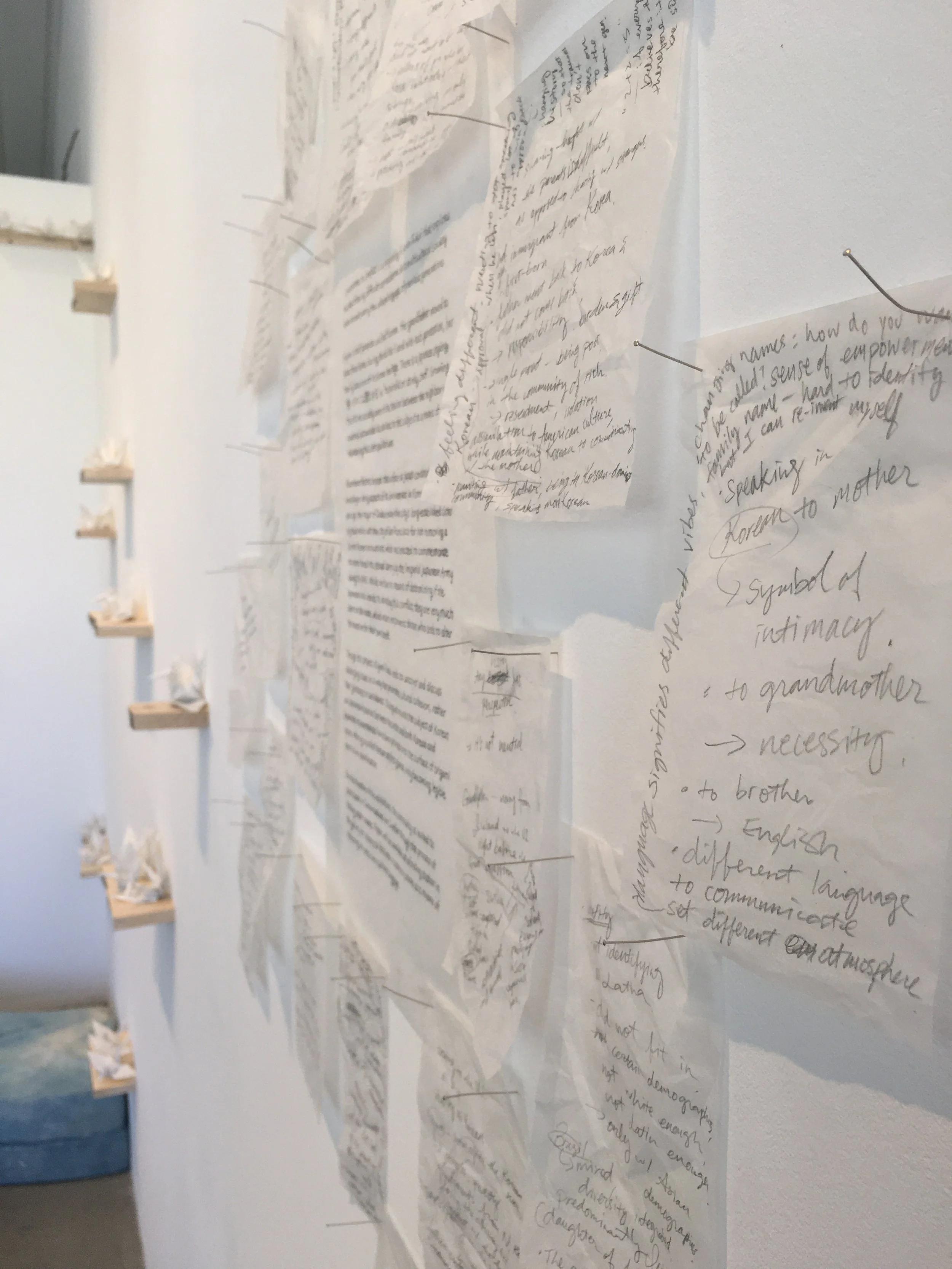

This summer, I embarked on the journey of having a series of difficult conversations around the topic of how a large historical moment (such as the Pacific War) has a lasting effect on individuals through different generations. I picked Korea as my personal starting point, as I felt called by the subject. It could be the radio news I heard a while back about comfort women, or it could be the troubling historical narrative found in Japanese textbooks. Japan has been accused of re-writing its own recent history regarding these war times. “Re-write” is actually not quite accurate, as the rhetoric is much more complicated. They are not outright denying such events and instances occurred (i.e. comfort women), but rather tweaking the description and discussion to alter the weight of what happened. In either case, I could not help but feel repulsed and completely lost, seeking what the true history was.

I had talked to a couple Korean friends, each with their own interesting history, before I decided to reach out to my dad. One, who wishes to stay anonymous, came from Korea to the U.S. as a first-generation immigrant when he was a student. He enlightened me with the current political climate of Korea, as well as how it came to be, through its history post-Korean War. Another, who grew up in Germany, told me about how and why her mother immigrated to Germany, tracing her other family member’s story, and her own story through the conditions of the time. This conversation lead to the idea of historiography — who gets to write history? To tell a story is to preserve history — our own personal history.

These conversations made me confirm that I was indeed fascinated by an individual history, not the grand narratives told through textbooks. Then an idea sparked in my head: What about the story of my dad, and his dad? Their lives were forever changed by this extraordinary historical moment, though differently in each generation. It is so easy for my generation to feel that our individual life is independent from history, but it is not. Everything is connected.

For the record, I don’t talk to my dad as frequently as I should. The last time we actually spoke on the phone was probably around the fourth year anniversary of my mother’s passing. He is a retired pastor of Seventh-Day Adventist church. He is conservative. He does not tolerate other religions, other sexual-orientations, or things that seemed too “secular” to him. I often could not tolerate his intolerance. We had argued quite a bit in the past, and I became more and more comfortable simply avoiding talking to him altogether. The religious talk does surface in our conversation a little bit, but not as much as I had expected. He was mostly pleased that I was interested in his story. He actually researched and kept a detailed record of my grandfather’s experience, and sent me a 12-page essay on it (couple versions to be precise), prior to our conversation. We talked for closed to 2 hours that day, and I learned so much that I did not know about him; from his childhood to the process of naturalization, the meaning(s) of his name, to his view on Japan. His view, in my opinion, breaks my heart just a little bit, because I am Japanese. I wish things were different. I wish he did not have to experience the nuance of being Zainichi in probably the most difficult time to be one. I wish he could call Japan his true home as well. And above all, I wish we, the Japanese people do speak about our own issues and history. I do truly wish Japan could learn to see its history with much more compassion towards the others.

***

Kiyomi: So when I was presented with this opportunity to do a project, I thought about some possible topics I’ve been concerned with — one was about Comfort Women. About a year ago I heard this story on the radio, that the mayor of Osaka city decided to terminate a sister-city relationship with San Francisco over a Comfort Women statue there. This is a relationship that lasted about 60 years — it’s sort of like they went way out of their way to deny this issue. The story left me with couple of uncomfortable things to think about. One is that I, as a Japanese person, had no knowledge of this issue, which I found to be quite shameful, and the other, that this is in no way a good strategy in terms of reconciliation, or I guess to put it frankly, to ask for forgiveness. Another point of concern for me was an issue around a historical narrative; who writes history? Who gets to decide what is told, and who gets to deny history?

So in a way, this massive amount of documents you wrote, — I did not expect this much from you! It’s got so many pages —, this to me is your effort of preserving your history and your father’s. If you didn’t write this, it will only dissipate, and I think it’s one important task.

Teru: So which version have you read?

K: I read everything!

T: The one I sent yesterday? Already?

K: Yea the whole thing. I read it.

T: It was interesting, wasn’t it? You are in it too.

K: Right, I was caught off guard. And I have absolutely no memory of the episode. (laughs)

K: Oh yes and what I found interesting is that maybe about a half, no, a third of this new one is diaristic?

T: Well at that time, I felt the urge to leave a record or something — I decided it can be just about what I was thinking about to start with. The very first entry was from the time we all thought my dad was going to pass away, so it was while he was still alive. Also, this was not included in the document, but maybe a year before he passed away, you and your siblings went to your *1grandma’s in Iwate with your mom without me. I had work, I couldn’t go with you guys. So that’s when I got to spend some time alone with your grandpa. I thought it was a good chance to ask him for important stories and details of his life, but he said there’s nothing worth telling. But I persisted, so he started giving me little bits and pieces. The details about Kinryo-gakuin in the document, that came from this conversation. I actually wrote another entry right then and there, but it got lost, you know — I think it was from Apple upgrading the software. I think it was because I used to use egword, which was Mac’s version of Word, so when it wasn’t doing so well in the market, after Mac’s upgrade or something, I couldn’t open it anymore — those old documents were not compatible with the new OS. I suspect it was from then a lot of my old documents got lost or messed up. Anyway I had to rewrite about that episode later.

K: That’s the part about Kinryo-gakuin?

T: Yea, actually what’s in the new version is probably the rewrite from long time ago — I was surprised to find it. I’m sure the original might be some place, too, but I don’t know if I can recover it anymore. Well it’s all just me putting everything together, so to be frank I don’t think it’s organized for a good read.

Well it’s hard, because grandpa himself did not know the position he was in, or the meaning of the time he lived in — he was just getting caught up in the storm.

The other thing that makes this confusing is his siblings. They all have different opinions and recollections. So the first essay was written with that in mind.

You know, he has that pickles store in Fukuoka — kunabuji I call him, it means uncle in Korean. He told me we were not from a family of *2yanban (noble family). He said it was an absurd idea, and I was disappointed, as your grandpa would tell us we were.. But just the other day when I saw my brother, your uncle, he said Kunabuji told him long time ago, that we were actually from yanban family. It’s confusing, but we were speculating that maybe Kunabuji’s own memory has been changing over time. So in short, nobody knows what the truth is, since there was no concrete record to go by. I wonder if it was the people around Kunabuji who told him it was absurd that we were from yanban bloodline.

And our relative I found in Korea — I don’t think Kunabuji knew him either. I had a help from Korean police department finding him. Over there, after the Korean War, police took on a role to reunite separated family. It was actually miraculous that they were able to this person.

K: You mean this person you mention? The last name says 車, but I don’t know how you’d pronounce it.

T: Oh Sha Totetsu? I think you’d call him Cha Dong-chul in Korean. No that’s not him, Kunabuji knew him pretty well. In the same paragraph, I mentioned another person, Kim Taishun. That’s the person we found through the police. Kunabuji’s son, my cousin, didn’t know him either. This Taishun, too, denied that we were from yanban blood — back then you could call yourselves anything, in order to maneuver around the hardships. So he convinced me a bit that maybe your grandpa made a mistake, and we are not yanban after all — but we actually don’t know that either. The biggest issue for me was this person himself. I met him twice, but I found he was an alcoholic — all the money I gave him, he’d use it for alcohol. Unfortunately his brother was also the same way.

K: So would he be your cousin then?

T: He’s Kunabuji’s older brother’s son. I think I sent you a family tree as well — your grandpa was the youngest. Kunabuji is the second youngest. And you’d see the oldest son all the way at the top.

K: Let me bring it up, hold on..

T: So when you look at it, the very top is Kim *3Chuka, pilar and flower, 柱華. And next to it, you see Bok Shoko. This person, she’s my grandmother, your grandpa’s mother. Under this couple, you see six lines — the left-most side is Kim Chigen, born 1917. That’s your grandpa. Next to him, Kim Kigen, that’s Kunabuji, Kim Myoko, the one next to it, that’s his sister. Kim Huan is also female, and the Kim Shuk, that’s female too. And the one next to it, can you see Kim Segen? It’s similar in Okinawa too, but in Korea they use the same Chinese character to name male siblings, in this case, gen 炫. So this Segen is the oldest son, and from Korean tradition, after Chuka died, he was in charge of the household, and had more power than the mother. Do you see the youngest of Segen’s children, Taieki? I met him once, too. It was early in the day, but I could tell he was already drunk.. After interacting with these two, I came up with another theory — maybe it wasn’t that Kunabuji didn’t know about them, but he just didn’t get along with them. They might have been asking for money and stuff.

K: Well you know I read in one of your essays, I think it’s the new one you sent, that the oldest brother brought home someone to appraise everything they owned and liquidated their possessions.

T: That’s what I heard had happened. That he was in charge of everything, and that’s what he did. However, there is something I still don’t know clearly. Someone once told me that your grandpa had seven siblings. Only six, including him, are listed here. So what about the other two? Right? One possibility is that the two had already passed away long ago. We don’t know. Taishun said there were only these six. Anyway it’s that unclear — even the number of siblings, or where they went.

K: Well you did mention in your essay that the record has been pretty unstable.

T: Yea you know in Korea, the government itself was very unstable, even before Japan’s occupation. One could argue that Japan took advantage of unorganized form of government — or it certainly didn’t help. And of course, the Korean War that started in 1950 further messed up any records that was left.

K: This actually was probably the most interesting part of your writings though. In this confusion, you try to untangle some threads and uncover the history. You include some personal encounters, like the apples being not as hard as you were imagining to be. This process and journey was the most exciting part for me.

And can I ask, if you felt you being yanban was partly an emotional support of some sort?

T: Well of course, both my brother and I, secretly was proud to think that we were from a noble family. (laughs)

Korean royalty, you know, Kudara, Kokuri, Shiragi — Shiragi came from Kinsen, where your grandpa was from. And he’d tell us we were from the royalty. (laughs)

K: This inquiry started with my questions about my grandpa, but I actually grew more and more curious about how you grew up in Japan after the war. Especially on discrimination you probably received as a Zainichi Korean.

T: You know, about that, I actually have been thinking of writing on that, after I’m done writing about grandpa. It touches on what made me want to pursue God, or made me hate God at times. I used to wonder why He would leave Japan alone, or allow it to thrive, even after the horrible things they’ve done, and actually continue to discriminate against Koreans. I was angry when I was a student — middle school, high school, especially high school. Even when I was in grade school, if they found out that you were a Zainichi, you had to move. One time, I think I was in the first grade, I didn’t know what being Korean meant, or even what Korean was. I thought it meant some sort of an alien, you know like Gekko Kamen. Gekko Kamen is this masked hero, like Iron Man in the United States. I thought it was something like that. So some kid came up to me, and asked if I was Korean. I didn’t know if that meant good or bad, so I said yes I was, like I was an alien from the moon, almost bragging. I think the kid just ran away. (laughs) But later I found out that wasn’t a normal thing to do. You’d be hiding that you were Korean. If people found out that you were, they wouldn’t want to be your friends. So you know at home, we never spoke Korean. Grandpa didn’t want us to even learn. He wouldn’t say our last name was Kim 金. He’d use Kaneshima 金島 instead. So my name was Kaneshima Shinki. My real name was *4Kin Shinki. Mine was the special case though. My brother’s Japanese name was Kaneshima Yoshihide, like Toyotomi Hideyoshi. His real name was Kin Ekiki. Mine was Shinki and grandpa didn’t give me another Japanese name for some reason. Ekiki probably did not sound Japanese enough, so he had to come up with another one. My sister, Kin Mira, also sounded too Korean, so she had another name, Yoshiko. For me it was easy, as the only thing different was the last name. I just had to add shima. But it was more complicated for the other people, just by looking at my siblings’ names.

So through grade school to high school, we try desperately to hide our real names, so that they won’t know we were Koreans. You’d never know what they’d do to you. So you had to avoid the topic at all cost. If there was a news about Korea in newspaper, you pretend like you knew nothing, not interested. I think it was a first year in high school, we had an exam. I forgot if it was a mid-term or final. We were given answering sheet, then the questionnaire. And mine, there was a question that was strange. There was no way to answer it. I raised my hand, and told the teacher I could not answer it. He switched the sheet immediately, but I think I was the only one with the wrong sheet. That was one incident that stuck out to me — some teachers harassed Koreans like that. But there were also teachers who would ignore that we were Korean and tried to be as fair as possible. In fact, most teachers were like that in the high school I went. I think God was protecting me.

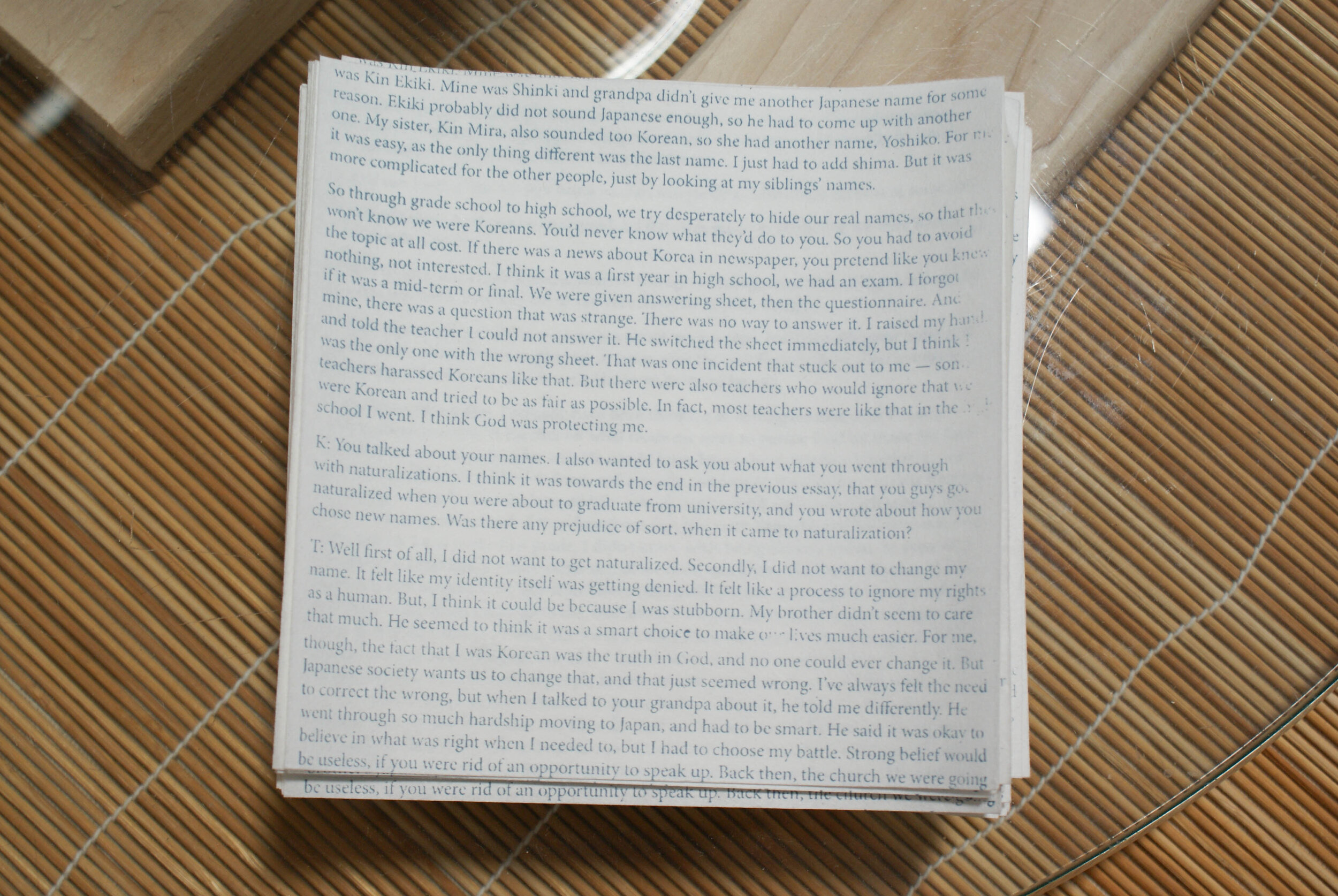

K: You talked about your names. I also wanted to ask you about what you went through with naturalizations. I think it was towards the end in the previous essay, that you guys got naturalized when you were about to graduate from university, and you wrote about how you chose new names. Was there any prejudice of sort, when it came to naturalization?

T: Well first of all, I did not want to get naturalized. Secondly, I did not want to change my name. It felt like my identity itself was getting denied. It felt like a process to ignore my rights as a human. But, I think it could be because I was stubborn. My brother didn’t seem to care that much. He seemed to think it was a smart choice to make our lives much easier. For me, though, the fact that I was Korean was the truth in God, and no one could ever change it. But Japanese society wants us to change that, and that just seemed wrong. I’ve always felt the need to correct the wrong, but when I talked to your grandpa about it, he told me differently. He went through so much hardship moving to Japan, and had to be smart. He said it was okay to believe in what was right when I needed to, but I had to choose my battle. Strong belief would be useless, if you were rid of an opportunity to speak up. Back then, the church we were going to accepted us for who we were. They understood that we were Korean, but living as Japanese, even though the government wouldn’t admit it. I felt comfortable, and I was able to be myself there. We were originally going to a church in Zainichi community, but they had much troubles, between their church members and their faiths, and so on. Anyway I was studying the Bible at that time, and I learned about Saul changing his name to Paul with no hesitation. He would change it according to who he was speaking to and the situation he was in. Another one was about Daniel, when he and his friends were taken to Babylon as slaves, and they were forced to change their names, like Belteshazzar, and these were the names of Babylonian gods. They probably were not happy with it, but either way it is in the Bible. When I heard that, I found them to be noble. Like grandpa said, true faith might require you to be smart, and accommodate what you can, and speak up when you actually need to. So we all decided to get naturalized — I mean I knew we wouldn’t be moving to Korea, I didn’t even speak Korean. I knew I wanted to visit there someday, but it won’t be a place to settle. With the timing that I was about to graduate from Kyusyu University, we thought it would give us a better chance to get approved, too. Without citizenship, there would’ve been too much troubles. They’d call you foreigners, you’d need to contact Korean government for documentations on every little thing, you can’t take out loans, you basically can’t do anything.

K: So I don’t know anything about this, but it seems being naturalized is not an easy process. Was there a chance you’d be denied?

T: To be honest I actually don’t know. I only know what my family went through. I’ve never looked into how difficult it is for everyone else, or studied laws around it. It all sort of depends on the attorney, too. It’s not really about the law, but who maneuvers around the law. If you don’t get a good attorney, you might be out of lack even if the law says yes, and vice versa.

At the Zainichi Korean Christ Church, I heard of some people who didn’t get approved, some being laughed at. And you know even if you did successfully get naturalized, your record still says “former Zainichi Korean” on it. So you try to get the citizenship in order to avoid prejudice, but you actually cannot get away from it. It’s like the law is requiring people to hold prejudice against us. What IS the point of naturalization then? In the U.S., you get to be their citizen the moment you are born there, like in your case. Because you were born there, you are an American. If you would’ve been born in Japan, that wouldn’t make you Japanese. You are only Japanese because I got naturalized. If I didn’t, you would also be called Zainichi Korean.

K: I did not know that — that sounds strange.

T: Citizenship system depends on country. The U.S. operates like Europe back when Apostle Paul was alive, like the Roman Empire. Rome was very international, and they would let you have a citizenship of where you came from. So Paul was Jewish and Roman citizen at the same time, because he was born in Tarsus. So he didn’t earn the Roman citizenship later on, but he was just born into it, like how it works in the U.S. In other words, the U.S. follows the Roman model to some extend.

K: I had no idea.

T: But in Japan, the system operates in order to exclude.

K: It’s meant to be exclusive.

T: Very much so. I actually don’t even want to describe it as exclusive. It’s beyond that — it’s discriminatory. It makes me angry whenever I think about it. That’s just my personality.

K: You know this is probably something no Japanese person thinks about, or even know about, going about your daily life and all.

T: Well you don’t ever have to think about your Japanese citizenship if you were born Japanese.

K: It honestly didn’t even occur to me.

T: It’s not like that in a country like the U.S., because it’s multicultural. You probably have a chance to think about your citizenship all the time, not in a bad way. Where you come from does not shame you. Although I am sure there are other forms of prejudice and discrimination, like racism against people with different color of skin.

K: Right.

T: That’s another topic — anyway that was why I did not even want to be Japanese.

The system lacks compassion, and I wanted to refuse that attitude. I am a stubborn person. But look at Daniel and his friends. Although the way Babylon operated was a lot closer to the States. They actually educated their captives, and allowed them to return to their homeland. Japan was never like that. They never grew out of that old attitude. They seemed to be more progressive on the surface, as they are starting to be more international, but not their law, or their system. I think it’d be very interesting if someone actually studies up on that. You know the Christian persecution in the samurai era? The attitude is still the same to this day. They seek to exclude the others — I just hate that. I think this is the kind of quality that denies people of human rights, what makes them human. We are not seen as equal from the moment we are born. How is that a human act? That’s actually what makes us non-human. Well that’s how I judged this country anyway.

T: That being said, grandpa told me that a true Christian needs to forgive. He told me not to put myself in a situation that doesn’t allow me to defend myself, and that it would be stupid to do so. If the situation is right, then I get to finally speak what I am thinking.

T: So we decided we would get naturalized, and we had to think of the names. I was thinking of keeping my real name, Kin Shinki. When I got into the University, I started using my real name.

K: So you didn’t use Kaneshima anymore?

T: No I went with Kin Shinki. It was easy, I only had to remove shima. But then now people thought I was a student from Korea, and that was another confusion I had to deal with. So people freaked out when I said I wanted to be naturalized as Kin Shinki. They thought Kin Shinki should not exist as a Japanese name. There is this famous thinker who graduated from Tokyo University, I think his name was Ho. He is also Zainichi. I admire him, he never changed his name.

K: How does that make you feel?

T: Well I admire that, but at the same time, I don’t think I could do the same in my time.

K: Oh I’m sure this generation must be much different.

T: Yes and also the environment. Tokyo University, or at an academic setting, speaking your thoughts out loud can still be treated with respect. The exact same thing you say could be scorned at among the non-educated people.

K: (laughs) I think that’s very relatable here in the States, given our current political climate.

T: That’s what grandpa meant by being smart. Avoid unnecessary conflict, but speak up when the time is right. Especially when you got a president like Trump, right?

T: Anyway that’s why we decided it’d be best if I changed my name. Grandpa wanted me to not even go with Kaneshima either. One reason is that grandpa named me Shinki because of this fortune-telling tradition. I always loved my name Shinki, but when I found out it was based on such superstitious belief, I felt betrayed by grandpa, because he was the one who always told us to keep pure faith with everything. So I remember criticizing him for that, I feel bad about it..

K: How about your brother? Did he have something to say?

T: Oh he said nothing. (laughs) Grandpa felt bad though — oh and he actually changed his name frequently.

K: Oh yea that’s something I wanted to ask you about. You wrote that he changed his name a few times. Does that mean he didn’t really have an attachment to his name?

T: Well that could be part of it, but more than that, he felt the need to change his name. I think he believed that his name dictated his fate to a certain extent. It could be from his Korean confucianism thinking. It’s actually a belief that spreads widely in many local religions, kind of like worshipping ancestors. So for him, he wanted to escape that by changing his name. First was Kin Chigen, and he changed it to Kin Shotoku, but he wasn’t completely satisfied with it. He was always insecure about his name, so we said let us stop that, and this would be a good chance to change his name one last time and get rid of the insecurity. So those were the reasons for changing our names.

And someone told grandpa that it’d be a great idea to borrow a Chinese character from the place they had been living at, which was the city of Fukuoka, so he decided to take the character fuku 福. Then he added a character that he liked, which was i 井, like a well. He wanted something to do with water, as he was always fond of the idea. So now we’d be a family of *5Fukui living in Fukuoka, it’s pretty funny.. (laughs)

K: Well I think it’d be more awkward to be a Fukuoka family living in Fukuoka. (laughs)

T: Yea well we were not going to complain any further. (laughs) Anyway when I was choosing my new given name though, I wanted to still keep Shinki. But you know, up until then, my name was Kin Shinki, with three Chinese characters 金 真輝. I thought it just looked good. Grandpa went with Fukui Kiyomitsu 福井 清満, with four Chinese characters. But I had a strong attachment to a name with three characters, so I went with Fukui Teru 福井 輝, and kept one of the characters, ki 輝 from Shinki 真輝. I liked shin too, I liked both characters. My brother went with grandpa’s new name, from Kaneshima Yoshihide to Fukui Mitsuru 福井 満, the same character from Kiyomitsu, means to be satisfied. So he actually ended up with three characters. He did not have that character in his original name, but he decided to go with it. Actually in the end, when you were born, your name Kiyomi is basically part of grandpa’s name Kiyomitsu just without tsu.

K: (laughs)

T: Oh he was so happy when you were born. I mean he might have been just happy with his new grandchild, and I don’t know how much your name had to do with it, but he covered all the cost for your birth. I was a student at the time, so we were very poor, although the cost was really cheap back then, like $1750 or something like that. It was super cheap, unthinkable — I mean we went home in half a day. (laughs) I think normal Americans would have stayed at the hospital for at least two or three days. But your mother was so hasty to go home to save money — half a day after giving birth! It’s impressive. I thought she was a fascinating person. I’m sure it wasn’t easy. But you know, I think back to those times, and wonder if her cancer came from those times when she pushed her body too much. I mean I don’t know, you know. We don’t know what caused the cancer, but I still feel guilty about how hard she worked.

K: Well I think it’s the kind of thing that’s out of our control.

T: Well we never know. Anyway, that’s how we became Fukui Kiyomitsu, Fukui Mitsuru, and Fukui Teru. I didn’t like my name though — I mean it was just unfamiliar, Teru. And you know Teru actually sounds like a lady’s name, too. I could have made it so that you’d read it as Akira instead, but I did not like Akira. To me it sounded to Japanese. I wanted to make it somewhat unusual name, I guess out of spite. (laughs) I wanted to leave some mystery, you know.

K: Huh, so now that you became a Japanese citizen, right? How old were you then?

T: That was when I was 24.

K: So how many years have you been Fukui Teru now?

T: Well, you know, it usually takes four years to finish college, right? But then that was the time of student activism, and the university was closed for more than half a year. Then they decided to resume the classes without notifying us, probably because if they had delayed it any further, they would have had to stay closed for the next school year. They actually made a decision to ignore the missed time, and still passed the students — academically speaking, I think it’d be considered fraud. They would have had to lose a whole crop of new students, you know. That was another thing that made me feel rebellious against the institution. I almost wanted to quit. But up until then, I prayed and studied hard — I did not want to feel embarrassed in front of God. So by the time I went back to school, I was out one year. And then I actually had to play catch up using another extra year. So altogether it took me two extra years to catch up, whereas the other students probably only spent 6-7 months. Those are the people who went back right away, when the university secretly re-opened. I took my time going back, and one year was not enough. I had a hard time adjusting back to school. Anyway normally you’d be 22 by the time you finish college, but I was already 24. So we got naturalized when I could be sure that I was graduating. You know when I applied, it took me only 1-2 months to get approved. It could’ve been one and a half month. After I submitted my application, they called me, told me it was approved, and that was it. For the reason of application, I wrote that I wanted to use my voting right. (laughs)

K: (laughs) Good thing!

T: It was! It showed them I’d be a good citizen. (laughs) And then, grandpa and my brother went to apply immediately after I got approved. It took only about 2 months for both of them.

K: Wait, so you guys didn’t apply all at the same time?

T: Well it’s because we had no idea how it would go. One person would go, and the rest would be easier, we thought. You know, you can just tell them “oh it’s because my son got naturalized”. But, my sister Yoshiko never got naturalized. She was living separately from us. She never gone through the process until she passed away.

K: When you say she was not living with you guys, you mean she was with her mother then?

T: Well not her birthing mother, but with grandpa’s second wife, who he divorced as well. So she went with her when they got separated. I mean our place was tiny. We didn’t even have a bathroom. Of course no shower. We used to put up a curtain in the kitchen to wash the body, but it’d get everything there wet — it just wasn’t too functional. I remember us fighting a lot, too. Also she was the only girl in otherwise all-male household, and she needed her privacy. The only female figure in our family was grandpa’s ex-wife, I mean it actually wasn’t a legal divorce back then, they were only separated. I believe they went through the legal process a lot later on.

K: I didn’t know he went through divorce twice.

T: Yea it was difficult back then. The first wife was never around home, she had a lover elsewhere, and she’d be sneaking out all the time. When grandpa found out, he thought he had no choice other than to divorce her. And the second wife, it turned out she was still married to her previous husband. I think the reason for this drama was because he was almost forced into marriage by listening to Kunabuji. Korean tradition is very confucian, and you must always listen to your older brother no matter what. So grandpa listened to Kunabuji, and he found out later she came with a baggage from her previous marriage that was not resolved properly. Grandpa thought it’d be wrong to stay with her in God’s eyes, and his believed that a big mistake like that would lead to God cursing him as a punishment. So he thought it needed to be corrected. Well they actually fought a lot, but he conveniently put that aside. Also divorce was not so uncommon in Korea back then. Different culture, different way of viewing marriage. Anyway I don’t know the whole picture, but that’s what I know. And then as Yoshiko grew up there, she developed a chronic disease, rheumatism. Poor Yoshiko, she suffered a lot. I felt terrible for her — this is actually why I still strongly believe in the health ministry. So I have something I want to do. The SDA church has been given a code of health, and it should not be taken lightly. It is a blessing, and cannot be ignored. Grandpa had a terrible health issue, and Yoshiko too. Your mom and her cancer was probably not from her lifestyle, but either way, it doesn’t hurt to do the best you can to take care of your body. So now that I am retired, I am studying health ministry, so I can help people put this knowledge into practice.

K: Now I’d like to ask you a question. Since you got naturalized when you were 24, I guess it’s been 45 years.

T: Yep I do think it was when I was 24.

K: Well even if it was a little off, it’s still been over 40 years.

T: Wait it’s not 35 years, it is 45 years then?

K: Yea 45! So if someone asks you what your nationality is, would you say you were Japanese, or would you still consider yourself as a Zainichi Korean first?

T: Well as my identity, I do think of myself as a Zainichi Korean. That part never change, but I can tell people I am Japanese with no hesitation. Before, I felt like I was lying a little bit. (laughs) Now I can actually say I am Zainichi Korean, but I am also Japanese, according to the law. But you know, there is this person at the church, and *6they’d be asking me “pastor, you are zainichi, right?”. With this particular person, I actually didn’t even want to give them an answer. I couldn’t tell what their intention behind that question. Why would they need to know that, and what use would they get out of it? It did not feel like this person was trying to get to know me better genuinely. So I thought they did not have the right to that information. There are some questions you can ask people, if you are being genuine, but otherwise you shouldn’t be asking someone something personal like that. Because this person didn’t want to actually know if I was zainichi or not, but they wanted to pretend like they knew — this leads to another prejudice, and that leads to exclusionism. There are people like that, who don’t wish to understand the other person as a whole, even in a church. It’s such a pity. You know I’d be speaking of my zainichi heritage a lot more openly if I was in the States.

K: Ha, I actually do know what you mean. When I was in Japan, of course I was aware that I was half-Korean, but I didn’t really talked about it there. But ever since I moved here, I never really shied away from the topic.

T: When I was studying in Michigan, so when you were born, whenever someone asked, I’d be telling them I was Japanese Korean or Korean Japanese or something like that. When I was talking to a curious Korean person, I said “my gene came from Korea, but my protein came from Japan”. (laughs)

K: (laughs) Makes sense.

T: They said that was a great way to put it.

K: You know this is what I find interesting — so you’re not Korean from Korea. You grew up in Japan, you don’t speak Korean. You got naturalized as Japanese, but your record still states you are a former zainichi Korean. So I imagine it was confusing to determine where you belonged to. Perhaps you feel differently about that now, but how about when you were younger, growing up?

T: So back when we were at the zainichi Korean church, they said your record will always indicate that you are a former zainichi Korean, even after naturalization. And they were right, my record does say that. So after people get naturalized, they gain all the same rights as the other Japanese people. You can vote and take out loans, but that does not remove people’s prejudice and discrimination. But, from my knowledge, if I change my address in the future, since that record pushes the previous one down, the indication actually goes away. But if you were to get your own record, I don’t think you’d see yourself as zainichi Korean, since you also have American citizenship. I’m just speculating here.

K: Hmm, okay, now, do you think you could forgive Japanese people, given all the situations you and other zainichi people have gone through?

T: By now, I don’t blame Japanese ‘people’. I am very much critical of Japan, and I cannot speak of it with pride, if I were to generalize everything about it. I know it sounds hateful. However, now when I think of Japanese people, I only think of the people I know personally, and they are good people. I can hardly think of a Japanese person with malicious intention. What I find malicious is just the laws and system of Japan.

K: I see. Was there any news on Japanese media about the Comfort Women statue in San Francisco?

T: The news framed it as the memorial being a false message, that it’s unacceptable that they have it there, and that it’s a scheme from Korean’s side. But the public probably at least understands that the comfort women did exist, but most of them also think that it is exaggerated and not a real issue. A lot of them probably are not perceiving it with a serious attitude.

K: They probably don’t know any details of each episode for an individual woman.

T: The truth is I don’t know their exact perception. But one thing I know is they are not looking at this issue from Korean point of view. I find that Japan as a nation has this nasty tendency to trash talk their surrounding countries, and the ones who talk loud like that stand out, especially in the media. I am sure a lot of Japanese feel a certain degree of dissonance for such talk. The nasty kind of people are rare in a church though, so I don’t have to deal with a tension like that in my day-to-day life.

I think there might be a better way that Korean government can deal with this, like taking it to an international court of some sort. But then, Japan is pretty sneaky, I’m sure they get defensive and point out other countries, that they are not the only ones with shady history. Russian soldiers did a similar thing, there was a violence and rape and stuff. But that’d be an issue of violence, as opposed to the comfort women issue, which was done more methodically in the military as an organization. That’s an outrageous issue. But they don’t talk about that, and they don’t even apologize. It’s like that recent issue with forced laborers during the wartime. Some Japanese corporations were getting sued to pay compensation to the families of those victims. Between the two governments, things are complicated because of this treaty they have, and supposedly everything was dealt with through that. Basically Japan paid them off so they can’t ask for any monetary compensations thereafter. But then the people who actually had to suffer or die, did so under the Japanese companies who were working them. So the treaty between the governments cannot just erase their sufferings. Just because the law says so, the victims won’t pretend it didn’t happen. It’s like trying to deal with something that has to do with civil law, but instead with criminal law. The nature of this issue is between the corporations and the civilians, it cannot be dealt with by anything other than civil law, right? I mean that’s just my opinion. In Korea, their position is that the individual loss and sufferings of the victims and their families have not yet been dealt with. But people don’t talk about that in Japan — they just think Koreans are still whining and asking for more money. The media here is not trying to communicate what Korean viewpoints are, because they are on the side of the government. Even the neutral-seeming media don’t know to be considerate of the Korean side of the issue.

K: It doesn’t sound like they have compassion in this matter.

T: If Japan does not learn to be more “human” — to recognize the true sense of equality, and not warp facts just to make themselves look decent, no countries will ever be able to forgive them. China, Taiwan, Philippines, everyone. That’s how I feel. Japan desperately wants everyone to *7put a lid on stinky stuff.

K: Well it doesn’t work that way though. The victims, who’ve been discriminated, suffered losses and all that, they can’t just ignore that it happened. How is it that we are dependent on them forgetting the past, so that we can forget about them?

T: The mentality actually is prevalent in the culture itself. When someone finds out that their family member has cancer, they seriously consider not telling the patient. In the U.S., it’d be considered unethical to keep it a secret, right? I think that is a difference in the attitude.

K: Well I guess it’s not a sign that we want to deal with the conflict head-on to actually resolve it.

T: Hmm, resolving might not be a good word, it’s a strong word. Humans are not capable of resolving everything. But it is an honest way to simply accept a fact as a fact.

K: In terms of forgiveness, it won’t be possible without accepting one’s fault.

T: That’s an interesting thought, maybe the foundation of Japanese religion does not stem from forgiveness, but rather to *8let water wash away. It’s to forget the past, which is different from forgiveness.

K: I see. You know, when us kids were little, there was this unsaid rule in our house that we couldn’t do anything too “Japanese”. We couldn’t wear any kimono, or have shichi-go-san, though that could just be from your religious standpoint. I think we tended to avoid things that had a strong connotation of Japanese culture.

T: I think you are right in some senses, though that wasn’t my intention. I was actually trying to avoid the influence of other religions like shintoism, and not the culture itself. But maybe that effort lended itself to be that way.

K: Well I guess I can see that was about religion now in the hindsight. Do you think there was a part of you somewhere though, that you wanted us to avoid being too “Japanese”? Maybe even subconsciously?

T: Could be. And I do feel bad for your mom for that — I know that wasn’t her wish.

K: How did she feel about it?

T: Mm, she never wore a kimono after we got married. Oh I guess there was one time, for her cousin’s wedding. Other than that, she didn’t though, and maybe that was because she was concerned about how I would react.

K: Well also it’s kind of a big deal to wear a kimono, so that could be another reason. (laughs)

T: I guess it could’ve been a financial concern too.

K: And you’d have to either know how to wear it, or pay someone who does.

K: Well, I definitely went heavy and personal with many of these questions. Thank you for taking your time for this.

T: Hmm, I always thought this is something you’ll have to deal with someday. So I was happy to hear that you were interested in knowing how and where we came from. It’s an important thing to think about.

K: Yea it’s all because I didn’t know anything. (laughs) That was the motivation.

T: Well it got me organizing all the information and episodes. Of course it is not done yet. But this did get me thinking who I am and why I am here. Also it’s my effort to remember what my dad went through, how difficult it was, and how God helped him through that. For that, this is an important task.

***

Endnote

*1 grandma’s in Iwate: my maternal grandmother

*2 yanban: grandfather used to tell his children our family line is from yanban (noble family).

*3 all names are read in Japanese pronunciation.

*4 Kin = Japanese way of reading 金. Kim is the Korean pronunciation.

*5 both Fukui and Fukuoka are the names of a prefecture in Japan

*6 they: In Japanese, a person is often referred to with no gender specification. I used the pronoun they/them to avoid making an assumption of the person’s gender.

*7 put a lid on stinky stuff: a saying in Japan. It means to sweep troubling matters under a rug.

*8 let water wash away: a Japanese saying. To let bygones be bygones.